Viktor Frankl – and the last remaining freedom

He experienced hell. But in the midst of it all, he also began to ask himself why some people do not give up even under the most terrible circumstances, while others collapse.

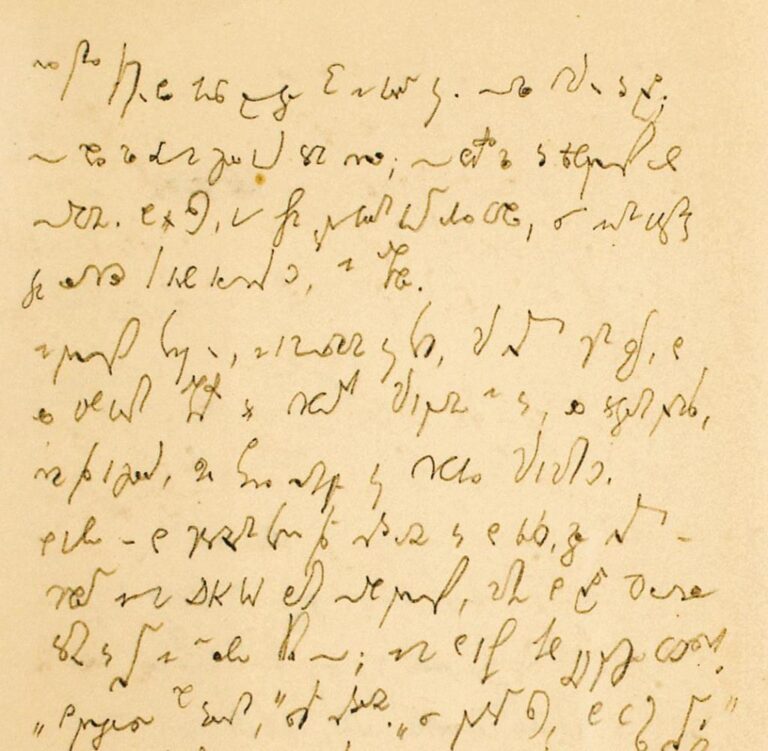

Viktor Frankl wrote: “Who among those who experienced the concentration camp would not be able to tell of those human figures who walked across the roll call squares or through the barracks of the camp, offering a kind word here, the last bite of bread there? And even if there were only a few of them, they are proof that everything can be taken away from people in the concentration camp, except: the last human freedom, to adapt to the given circumstances in one way or another.”

Frankl, founder of logotherapy and existential analysis, was born in 1905 and obtained doctorates in medicine and philosophy at the University of Vienna. In 1938, he was forbidden from treating so-called “Aryan” people. He then headed the last hospital in Vienna that still treated Jewish patients.

In 1942, he was deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp with his wife and parents. His father died there in 1943. His mother was later murdered in Auschwitz. His wife in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Frankl himself and the few of his fellow prisoners who survived were liberated by the US Army in 1945.

An impressive self-fulfilling prophecy

He tried to see himself as a witness. He wanted to survive so that he could talk about it later – that gave him meaning and the will to survive:

“Almost crying from the pain in my sore feet, which were stuck in open shoes, in the bitter frost and icy headwind, I hobbled in a long column the few kilometers from the camp to work. My mind was constantly occupied with the thousandfold little problems of our miserable camp life: What will there be for dinner this evening? Should I not rather exchange the slice of sausage that I might get as a bonus for a piece of bread? Should I trade the last cigarette that I have left from the “bonus” I got two weeks ago for a bowl of soup? How can I get a piece of wire to replace the broken one that I use as a shoelace? (…)

“I am already disgusted by this cruel compulsion under which all my thoughts have to struggle with such questions every day and every hour. So I use a trick: suddenly I see myself standing at the lectern in a brightly lit, beautiful and warm, large lecture hall, in front of me an interested audience listening in comfortable upholstered seats – and I am speaking; speaking and giving a lecture on the psychology of the concentration camp! And everything that torments and oppresses me so much is objectified and seen and described from a higher scientific perspective… And with this trick I manage to somehow place myself above the situation, above the present and above its suffering, and to look at it as if it were already a thing of the past and I myself, with all my suffering, were the object of an interesting psychological-scientific study that I am conducting myself.”

This is an impressive kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. By seeing himself in a better future, he was able to endure the horror – and so he was later able to actually give the lectures he imagined in the concentration camp.

In nine days he wrote his book “…Saying yes to life anyway. A psychologist experiences the concentration camp” – this is the German title, in English: “Man’s Search For Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy”. It is not only a report from the concentration camp, but also a trauma-coping and a powerful professional-psychological analysis of the human soul under the most extreme circumstances.

“Between stimulus and response lies a space. In this space lies our power to choose our response. In our response lies our development and our freedom.”

Many people know Viktor Frankl’s most famous sentences. However, it is definitely worth reading the entire report. We don’t just read terrible things. It is very touching to read how Frankl, in the midst of the horror, is completely filled with love for his wife. Although I don’t think the text should be reproduced in an abridged form, here is an excerpt: Throughout his life, Frankl worked on these themes: meaning, resilience and the possibility of living life with dignity even in the face of great adversity.

“While we stumble for miles, wade in the snow or slip on icy patches, always supporting each other, pulling each other up and dragging each other forward, not a word is spoken, but we know in this hour: each of us is now thinking only of his wife. (…) I have conversations with my wife. I hear her answer, I see her smile, I see her demanding and encouraging look, and – in person or not – her look now shines more than the sun that is just rising. A thought flashes through my mind: For the first time in my life I am experiencing the truth of what so many thinkers have drawn from their lives as the ultimate conclusion of wisdom and what so many poets have sung about: the truth that love is somehow the ultimate and the highest thing to which human existence can rise.”

(…) A comrade falls in front of me, causing those marching behind him to fall. The guard is already there and is beating them. For a few seconds my contemplative life is interrupted. But in an instant my soul rises again, saves itself from the here and now of prisoner existence.”

The inner world in the midst of external horror

Frankl writes: “The possible internalization even in life in the concentration camp also leads to the prisoner fleeing into the past: left to himself, his imagination is always occupied with past experiences, but not with the great experiences – the most everyday occurrence, the most trivial things or events of his previous life are often what his thoughts revolve around. (…) You take the tram, you come home, you unlock the door to your apartment, the telephone rings, you pick up the receiver, you switch on the electric light in the room – these are the seemingly ridiculous details that the prisoner caresses in his inner self. Yes, the wistful memory of them can move him to tears!

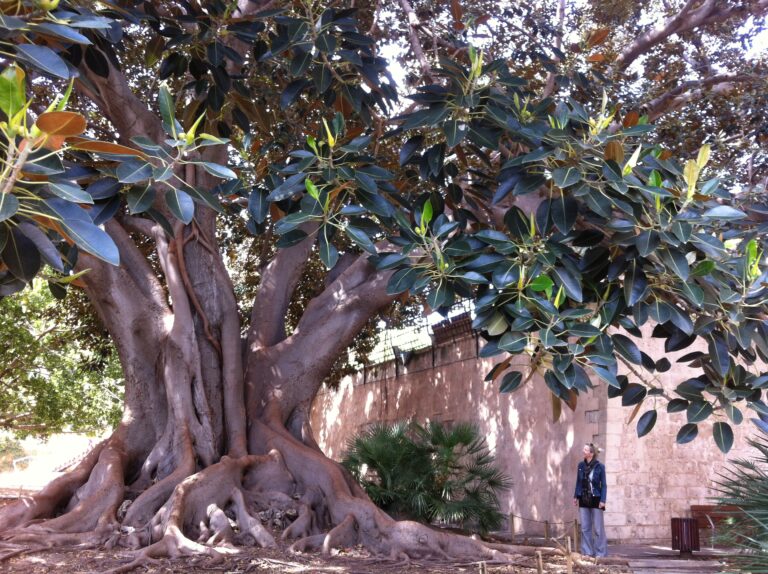

“The intensity of this experience can make him completely forget his surroundings and all the horror of his situation. Anyone who had seen our faces – beaming with delight, as we looked out through the barred hatches of a prisoner transport wagon on the train journey from Auschwitz to a Bavarian camp at the Salzburg mountains, whose peaks were just glowing in the sunset – would never have believed that they were the faces of people who had practically given up on their lives; despite this – or precisely because of this? – they were enraptured by the sight of the natural beauty they had been deprived of for years.”

Elisabeth Lukas, a student of Frankl, once emphasized in an interview: Frankl does not ask why someone becomes mentally ill, but rather a reason for getting well. Even before the Second World War, he worked as a neurologist and psychiatrist. What was completely new at the time was that he carried out follow-up examinations to compare mentally ill people with mentally healthy people. He found that both groups had the same amount of trauma. With this realization, Frankl abandoned Freud’s theory that history is the origin of all mental illness.

“Life is not primarily a search for pleasure, as Freud believed, or a search for power, as Alfred Adler taught, but a search for meaning. The greatest task of every human being is to find meaning in his own life.”

For Viktor Frankl, the origin of suffering was that those affected saw no meaning in life. When people experience meaning, they are more protected from mental illness. In the same interview, Lukas said: “Such a meaning cannot be set arbitrarily; everyone has to ‘feel it out’ for themselves.” If, for example, a politician stands up and says: ‘My meaning is to bomb the neighboring country because there is oil there’, that is not the meaning that Frankl means. According to him, people have a “pre-moral understanding of values” that kicks in before learned values come into play. He speaks of a kind of sense organ that allows us to sense meaning.”

For Frankl, even in the concentration camp, maintaining his dignity and helping other prisoners as best he could was what gave him meaning.

What is to give light must endure burning. Viktor E. Frankl

Not only did he work in the infirmary under the most adverse conditions, but he also tried to find consoling words for his fellow sufferers. This is how he once spoke to them in the dark of their barracks:

“And to give this ultimate meaning to our life here – in this camp barracks – and now – in this practically hopeless situation – that was the effort of my words. (…) I soon learned that this effort had achieved its goal. The electric bulb on a beam of our barracks suddenly lit up again, and I saw the miserable figures of my comrades, who were now limping over to my place with tears in their eyes to say thank you… But I must admit that I only rarely had the inner strength to rise to such final inner contact with my fellow sufferers as I did that evening (…).”

It is also noteworthy that Frankl had no thoughts of revenge after the Second World War and always protested against the concept of collective guilt. This too, not out of theoretical thoughts, but because of his experiences:

“The camp elder of this very camp, however, a prisoner, was tougher than all the SS guards in the camp put together; he beat the prisoners whenever and wherever and however he could, while the camp commander, for example, never once raised his hand against one of “his” prisoners, as far as I know. One thing is clear from this: labelling a person as a member of the camp guard or, conversely, as a camp prisoner does not say anything at all. Human kindness can be found in all people, even in the group whose blanket condemnation is certainly very obvious. The boundaries overlap! We must not make it so easy for ourselves that we declare: some are angels and others are devils.”

So what is man? He is the being that always decides what he is. He is the being that invented the gas chambers; but at the same time he is also the being that walked in the gas chambers, upright with a prayer on his lips.

The best chess move in the world

Frankl describes how differently meaning can be expressed:

“This meaning can now be fulfilled in three ways: either creatively, by creating a work, by taking an action. Ode r but experiencing, by experiencing the beauty of nature, the goodness of a person. Or loving a person, experiencing him in his innermost being. Thirdly, where it is necessary, where the cause of a situation of suffering can no longer be eliminated under any circumstances, it depends on the attitude and mindset with which we accept the suffering: with courage and with dignity.”

In our podcast we picked out a metaphor from Viktor Frankl that could help us in difficult situations – especially when making decisions.

We are used to thinking very generally and fundamentally about the meaning of our lives. Or we compare ourselves with other people. And then we lose ourselves. We need the next step. How do we find it? Whenever we compare ourselves with others, we choose a certain aspect – I want to look like this person – I want to be as creative or as successful as this person … and so on. But we don’t see the whole picture. We don’t see the whole path we have taken and the completely different path that someone else has taken. From the beginning to today.

Viktor Frankl said: “A universally valid, binding life task must actually seem impossible to us from an existential analytical perspective. From this perspective, the question about “the” task in life, about “the” meaning of life, is pointless. It should seem to us like the question of a reporter interviewing a chess world champion: And now tell me, dear master, what is the best chess move?”

Asking about the meaning of life is just as pointless as asking about the best chess move in the world. There isn’t one.

It depends on a lot of things – on the game situation. On the opponent. On the positions. So you can’t answer it like that. There is no best chess move. There are infinite possibilities, as long as you look at it fundamentally. Or at least a few million. But in a certain situation, suddenly only very few possibilities remain. Maybe just one.

So we don’t have to think about the meaning of life. We can try to find out what the best next step is. Try to see the whole path. Where we came from. What the situation is. What is relevant now. This may lead to the next step.

Viktor Frankl (1946): “Man’s Search For Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy”