Erich Kästner and our “Therapeutic Medicine Cabinet”

First episode – Simone

From February 2025 onwards, we will be launching our podcast “Metameaning”, where we´ll inquire into the topics that we also address here on the website.

A few weeks earlier we were invited to “Shrinking Trump”, the podcast of our wonderful friends Dr. Harry Segal and Dr. John Gardner. The exchange was so beneficial and inspiring that we wanted to continue in some form – also because we could read in the comments how many people find the podcast helpful and how much support it gives them in these difficult times.

That’s why we wanted to find a format ourselves that offers emotional, therapeutic, spiritual support to deal with the crisis of meaning as a result of the global meta-crisis.

We want to create a space to deal with grief, fear and stress. A space to be able to differentiate between reactivity and response-ability in one’s own behavior. To remain present and loving and to be able to act wisely. To collect supportive, helpful, but also creative things.

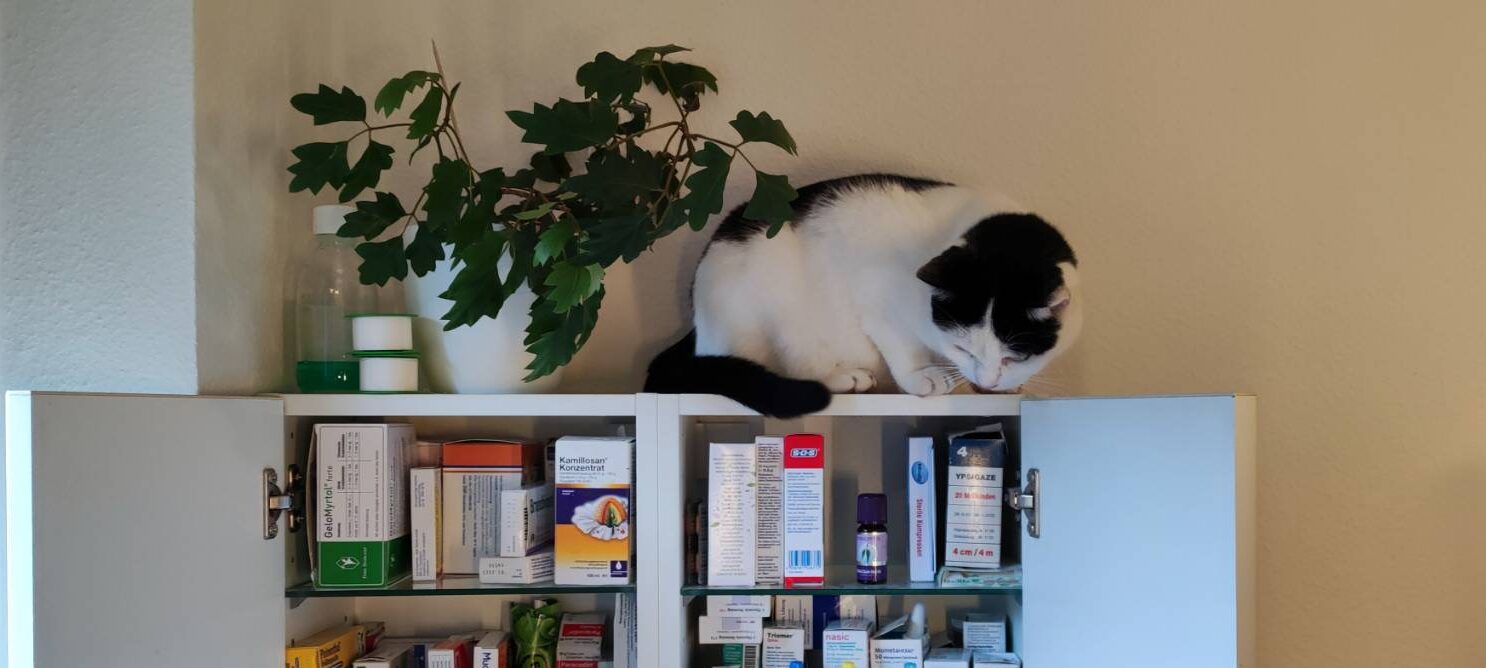

In each episode, we would like to explain one or two terms or concepts that illustrate different aspects of the meta-crisis, e.g. fear versus basic trust, “bullshit” (according to H. Frankfurt) vs. love and value of truth, or as mentioned, reactivity versus response-ability… etc. This section of the podcast is called “Therapeutic Medicine Cabinet”, analogous to Erich Kästner’s “Lyrical Medicine Cabinet”.

In 1936, Erich Kästner published a volume of poetry that he humorously called “The Lyrical Medicine Cabinet”. In it, he writes: “It feels good when someone else expresses your own sorrow. It is also pleasant to learn that others are no different and no better off than we are.”

Kästner plays with the metaphor of the “medicine cabinet” to illustrate that poems can be a remedy for the soul and can offer comfort, joy and insight – just as medicine is supposed to alleviate physical or psychological suffering. In this collection, Kästner deals with various topics such as love, loss, social issues and human existence, he names ailments, both physical and mental, as well as the respective pages in the book that should be read to alleviate the suffering.

Kästner expressed the idea of the “mental usability” of poems as early as the 1920s, and most of us have certainly experienced how comforting, how soothing and valuable a poem – a novel, a few lines, a picture, a piece of music – can be when you find yourself in it.

Marcel Reich-Ranicki had a similar experience with Kästner’s poems; the “Lyrical Medicine Cabinet” helped him get through difficult times in the Warsaw Ghetto. His girlfriend and later wife Teofila copied the poems for him and illustrated them in color. They offered him comfort, hope, and an escape from the cruel reality he experienced in the ghetto, writes Reich-Ranicki in his autobiography.

Even though Kästner somehow came to terms with the National Socialists – and had to come to terms with them –, he too lived in uncertainty and fear. He was arrested and released several times. His books were banned and burned; on May 10, 1933, he saw the book burning in Berlin.

After that, he was only able to publish in Switzerland – including “Dr. Erich Kästner’s Lyrical Medicine Cabinet” in 1936.

From 1941 until the end of the war in 1945, Kästner secretly wrote down what was happening around him and at the front: The Blue Book, his “Secret War Diary”, which I am currently reading, brings this time, which we are reminded of so often these days, vividly and frighteningly close.

One of his poems (around 1930) is also appropriate for the current situation:

Whatever happens:

You must never sink so low,

As to drink from the cocoa

That others use to pull you through!

This translation tries to preserve the meaning and message of the original, although it may not fully reflect the poetic structure of the original. In German, the phrase “pull you through the cocoa” is a play on words. The english expression “pull someone’s leg” comes rather close to it, but perhaps the meaning in Kästner’s poem is darker, more than just a joke in a humorous or playful way. Cocoa (“Kakao” in German) is as similar as sh*t is to chocolate – in terms of the sound of the word and color. So, you are literally dragged through the sh*t. The bon mot is meant politically first and foremost, the allusion to the Nazi “Brownshirts” seems obvious.

Perhaps this poem is a kind of warning and encouragement, not only to his readers, maybe Kästner wanted to remind himself to maintain integrity and his own convictions in the face of the most difficult social and political conditions. Not to become a follower. Kästner tried to be a chronicler of his time, and he formulated the declared intention of his notes in the “Blue Book” in his first entry on January 16, 1941:

“The decision has been made. From today onwards I will record important details of everyday life during the war. I want to do it so that I do not forget them, and before they are generally forgotten, changed, interpreted or reinterpreted, whether intentionally or unintentionally, depending on how this war turns out.”

Even if after the war, Kästner was not able to create a fully worked-out book from the diary, as a contemporary document it is powerful and very valuable.

Witnessing – this could be one of the terms that will become important for the therapeutic medicine cabinet and which we will discuss later. Stay with us!