Erich Kästner: “The Blue Book” 1941-1945

… and the “Lyrical Medicine Cabinet”

In 1936, Erich Kästner published a volume of poetry that he humorously called “The Lyrical Medicine Cabinet”. In it, he writes: “It feels good when someone else expresses your own sorrow. It is also pleasant to learn that others are no different and no better off than we are.”

Kästner plays with the metaphor of the “medicine cabinet” to illustrate that poems can be a remedy for the soul and can offer comfort, joy and insight – just as medicine is supposed to alleviate physical or psychological suffering. In this collection, Kästner deals with various topics such as love, loss, social issues and human existence, he names ailments, both physical and mental, as well as the respective pages in the book that should be read to alleviate the suffering.

Kästner expressed the idea of the “mental usability” of poems as early as the 1920s, and most of us have certainly experienced how comforting, how soothing and valuable a poem – a novel, a few lines, a picture, a piece of music – can be when you find yourself in it.

Marcel Reich-Ranicki had a similar experience with Kästner’s poems; the “Lyrical Medicine Cabinet” helped him get through difficult times in the Warsaw Ghetto. His girlfriend and later wife Teofila copied the poems for him and illustrated them in color. They offered him comfort, hope, and an escape from the cruel reality he experienced in the ghetto, writes Reich-Ranicki in his autobiography.

Even though Kästner somehow came to terms with the National Socialists – and had to come to terms with them –, he too lived in uncertainty and fear. He was arrested and released several times. His books were banned and burned; on May 10, 1933, he saw the book burning in Berlin. After that, he was only able to publish in Switzerland – including “Dr. Erich Kästner’s Lyrical Medicine Cabinet” in 1936.

About six years earlier he wrote the following poem:

Whatever happens:

You must never sink so low,

As to drink from the cocoa

That others use to pull you through!

This translation tries to preserve the meaning and message of the original, although it may not fully reflect the poetic structure of the original. In German, the phrase “pull you through the cocoa” is a play on words. The english expression “pull someone’s leg” comes rather close to it, but perhaps the meaning in Kästner’s poem is darker, more than just a joke in a humorous or playful way. Cocoa (“Kakao” in German) is as similar as sh*t is to chocolate – in terms of the sound of the word and color. So, you are literally dragged through the sh*t. The bon mot is meant politically first and foremost, the allusion to the Nazi “Brownshirts” seems obvious.

Perhaps this poem is a kind of warning and encouragement, not only to his readers, maybe Kästner wanted to remind himself to maintain integrity and his own convictions in the face of the most difficult social and political conditions. Not to become a follower.

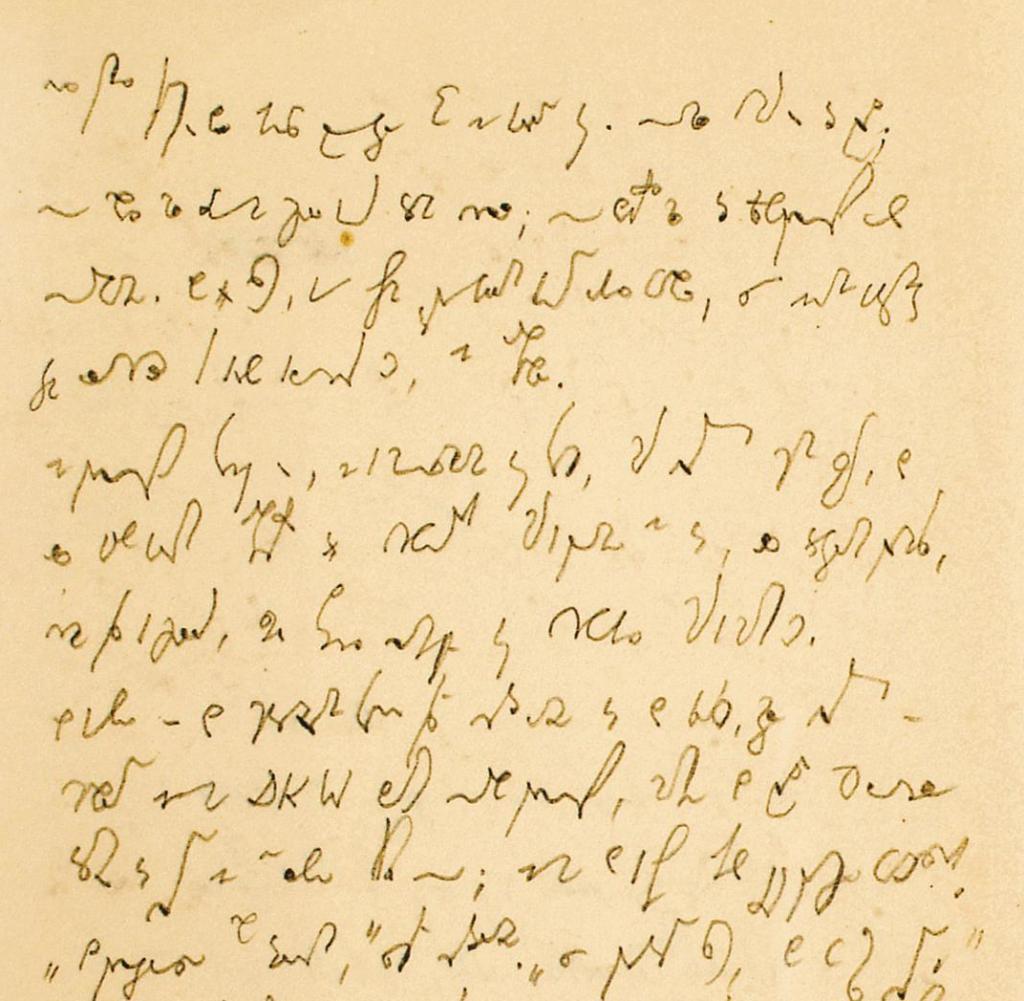

The Blue Book – Secret War Diary 1941-1945

From 1941 until the end of the war in 1945, Kästner secretly wrote down what was happening around him and at the front: The Blue Book, his “Secret War Diary”, which I am currently reading, brings this time, which we are reminded of so often these days, vividly and frighteningly close.

Kästner tried to be a chronicler of his time, and he formulated the declared intention of his notes in the “Blue Book” in his first entry on January 16, 1941:

“The decision has been made. From today onwards I will record important details of everyday life during the war. I want to do it so that I do not forget them, and before they are generally forgotten, changed, interpreted or reinterpreted, whether intentionally or unintentionally, depending on how this war turns out.”

Witnessing is certainly something we will be talking about more often and something that helps people find meaning in difficult times.

Here are a few more excerpts from Kästner’s notes:

“It is worth telling about Baldur von Schirach’s failed speech to the workers of a factory in Floridsdorf. They exaggerated their enthusiasm to the point of irony, so that they sang the movement’s songs for two hours without a break and burst into cries of victory, so that Baldur, after waiting on the speaker’s podium for two hours, finally went home without saying a single word.” Erich Kästner, The Blue Book, January 23, 1941

“What has really been in abundance in the last few months are: champagne, lobsters and orchids. There is less champagne at the moment than ever before. But there are still orchids.” The Blue Book, May 13, 1941

Every day there are situations where the absurdity of the situation just flattens you, as if you were being squeezed like a flower by an idiotic giant. The people in charge are sitting together somewhere, (…) knowing that there is no victorious way out, and waiting, picking their noses, for one German city after another to be turned into Pompeii.” The Blue Book, August 12, 1945

“Refugees are to be housed in Ketzin. But many already seem to be resisting. The same is true of the consideration shown for amputees in overcrowded public transport. People’s patience is now beginning to wear thin. It’s a shame that this exhaustion is being expressed against the weak.” The Blue Book, February 27, 1945

Then, in the last days of the war:

“May Day! Thick snow! The flowers are covered. The pink apple blossoms peek out from the snow like strawberries from whipped cream. Himmler is negotiating with Bernadotte about surrender. Hitler is said to be dying. Göring is said to be playing with toys and babbling. Munich seems to have surrendered without a fight. The Americans are at Mittenwald.” The Blue Book, May 1st, 1945

“The Americans all look like locksmiths or boxers. From Los Angeles, from Chicago, etc. One threw a barely smoked Chesterfield into the dirt. That impressed everyone.” The Blue Book, May 5th, 1945

And, one day before the war ended with Germany’s capitulation:

“The Russians report that the bodies of Goebbels, his wife and his children have been found in Berlin. The cockchafers flutter against the illuminated night window.” The Blue Book, May 7th, 1945

On July 29th, 1945, Kästner speaks at length with a visitor, a prisoner “dressed in an American uniform” who had escaped from the concentration camp, Männe Kratz. He survived Auschwitz, Ebensee and Melk and reported to Kästner in great detail about the events in Auschwitz, the mass gassings, the special prisoner commandos, the selections, the medical experiments – Kästner’s diary abruptly ends with the entry about this encounter.

Even if Kästner was not able to create a fully worked-out work from the “Blue Book” after the war – as a contemporary document it is powerful and very valuable.