With the ships we Invented shipwreck

We actually know that all life is in process, in motion – but we think and act every day as if the world was static and stable. We cling to supposed certainties, to our worldviews, our personal, social, and national identities – and are reluctant to acknowledge how fragile they are.

The Apocalypse is always perspectival

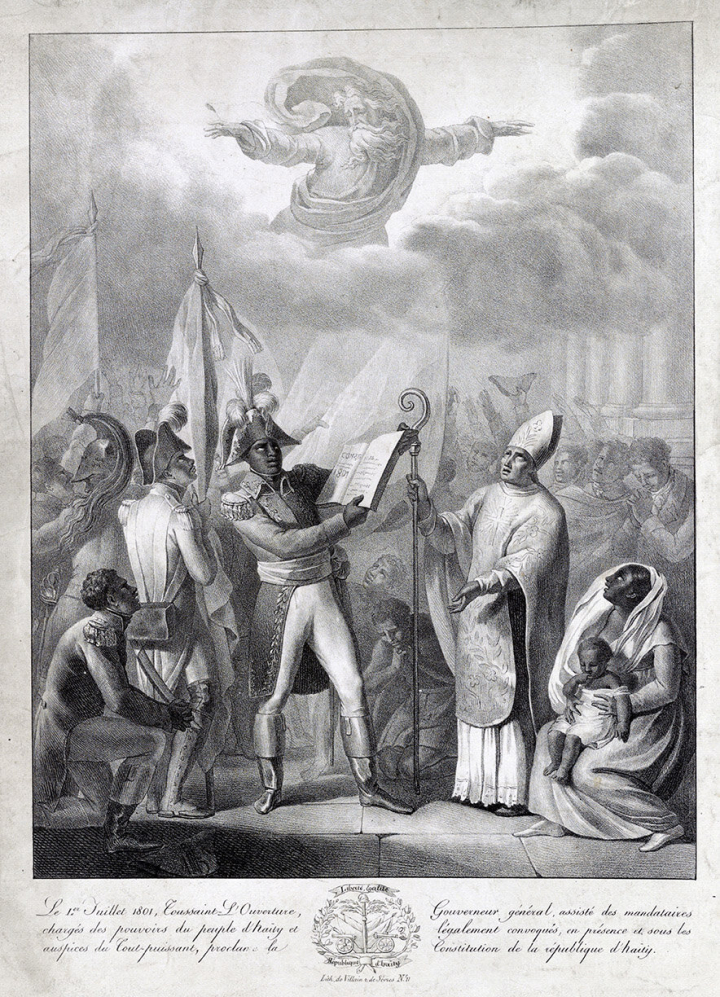

Comedian TJ recently said in one of his shows: “English is my third language. I speak Haitian Creole because I’m Haitian, and French because there used to be a big “foreign exchange program” in Haiti” – and by this, he’s not referring to student exchange programs, but to slavery (more on Haiti’s history here).

“Saint-Domingue,” as the colony was then called, was extremely profitable for France; slaves made up almost 90% of the population. The comedian is playing here with a topic that makes many uncomfortable. But he immediately adds that this isn’t (just) about Black people; it happens and has happened all over the world: people take over other countries and cultures and then force them to speak their own language. TJ: “Here´s what I found out. If your language and your nationality are the same – you did not suffer too much. If your language is different from your nationality, yeah, that’s not good – at some point in history, you were overrun. So for instance Koreans speak Korean, Japanese speak Japanese, but Mexicans don’t speak Mexican. Spain had one of the largest foreign exchange programs of all time. They were just giving Spanish to everyone, like it was a sexually transmitted disease.

Sophie Strand, a young American ecofeminist and writer, explores the connection between spirituality, narrative, and ecology in her work. She writes: “Apocalypse is always perspective. Most indigenous people are post-apocalyptic. People who were brought here on slave ships are post-apocalyptic.” Seen in this light, many people live in an apocalyptic or post-apocalyptic world – this is also the point of the comedian TJ´s bitter joke.

Migrants who have fled on extremely dangerous routes, losing their homes, their families, everything they knew – for them, the apocalypse is happening right now. In many parts of Gaza, the destruction is so extensive that there is no infrastructure left, no roads, buildings, or landmarks, so that even people whose homeland this is – or was – can no longer orient themselves. It is an apocalyptic world in which they struggle to survive.

Life in the Post-Apocalypse

From a geological perspective, we are living in a post-apocalypse. According to current knowledge, there have already been at least five major mass extinctions on Earth. For example, around 66 million years ago, 75 percent of all animal and plant species died out with the dinosaurs.

The sixth major mass extinction is now occurring (Global Report of the IPBES, 2019). One million species are acutely threatened with extinction within the next few decades. The annual extinction rate of plant and animal species is now ten to several hundred times higher than the average over the last 10 million years. And this trend is very likely to continue accelerating.

“Compared to previous mass extinctions, which could last for several thousand years, the current species loss is occurring at a rapid pace. According to the Living Planet Index (LPI) report from 2022, monitored wildlife populations show an average decline of 69% between 1970 and 2018, suggesting that natural ecosystems are degrading at a rate unprecedented in human history.”

More than 99 percent of all organisms that have ever existed on Earth are extinct. While this is devastating for many species, it also enables new life: The fifth mass extinction, for example, wiped out non-flying dinosaurs – enabling birds and mammals to rapidly spread and diverge into new species. And it clearly enabled nature to create humans.

Not only extinction, but also ubiquitous death and composting are essential to life on Earth: If organisms didn’t decompose and become food for other life forms, the Earth would be covered with plant and animal corpses.

Decomposition is also food production. What rots becomes food for others—for microbes, bacteria, nematodes, and saprophytic fungi that break down dead organic matter. They all have plenty to eat.

The Carboniferous Period

If organic material doesn’t rotP if decomposition doesn’t occur, then an element in the cycle is missing – a good example of this is the period we now call Carboniferous. Coal deposits were formed during this geological period – hence the name Carboniferous. Coal is now mined where swamps and bogs with dense vegetation existed during the Carboniferous period.

At that time, about 300 to 400 million years ago, there were no white rot fungi (weather rot) that could have efficiently decomposed lignin, one of the main components of wood. As a result, this robust material from dead trees continued to accumulate. It was deposited, turned into peat, and finally, in a geological process lasting millions of years, into coal.

The huge amounts of organic material at that time removed CO2 from the atmosphere so quickly and intensively that it led to global cooling – which contributed to a major ice age and a mass extinction.

It is truly symbolic of the complex processes of life that the compacted, non-rotting, non-decomposing trees of the Carboniferous period became our fossil fuels: coal, oil, and mineral gas, which – burned in today’s enormous quantities and at such a rapid rate – lead to the opposite: to the warming of the planet, which in turn contributes to mass extinction.

We are Energy-blind

Nate Hagens explains these connections very clearly and impressively in his podcast “The Great Simplification.” In a superb animated series, he describes the development:

“In the early 19th century – ten thousand years after the Agricultural Revolution—humans discovered how to extract fossil energy and materials from the earth to fuel their economies. This new discovery of coal, oil, and gas changed everything. Combined with a machine, a gallon of gasoline can do the same work in a few minutes as one person working for a whole month. Thus, to the work output of approximately five billion people today, we add the power of machines powered by fossil fuels – equivalent to the output of five hundred billion human workers.

The most important drivers of the economy were now virtually free: the only thing to pay was the cost of extraction. Not the cost of their production, their millions of years of history, their true, unique value, or the increasing pollution.

To our ancestors, harnessing fossil energy would have seemed like magic. And instead of seeing this as an incredible, once-in-a-lifetime stroke of luck, we told ourselves and the world that this newfound wealth and progress was a blessing in disguise. are due solely to human ingenuity.” – Most people are probably still convinced by this narrative today. Nate Hagens calls this “energy blind.”

One day, the costs of this type of energy production will be so high that it no longer makes sense – we will need too much energy to extract fossil fuels from the earth. Even renewable technologies, such as solar and wind power, increase our overall consumption instead of reducing the use of fossil energy worldwide. This is where the Jevons Paradox comes into play, named after a 19th-century economist, Walter Stanley Jevons. He was the first to describe how more efficient use of a raw material leads not to a reduction, but rather to an increase in its consumption (today we speak of the rebound effect): Overall consumption increases even though the consumption of each individual application decreases. Coal consumption increased after the introduction of new steam engines, even though they were more efficient than their predecessors. As a result of these innovations, the use of steam engines in transport and industry increased, coal became cheaper, and this led to higher coal consumption overall.

The Jevons Paradox

Humans are becoming about 1.1% smarter – that is, more energy-efficient – in their use of energy each year. Coal-fired power plants use less coal to generate the same amount of electricity. We invent solar panels, our televisions and washing machines are slightly more energy-efficient, and we conclude that we use less energy overall. But the savings are spent on other energy consuming. New innovations lead to significantly higher energy demand throughout the system. Since 1990, we have increased energy efficiency by 36%, while at the same time, energy consumption has increased by 63%. So, as long as growth is our goal and our cultural pursuit is for profits in GDP, greater energy efficiency will, paradoxically, unfortunately lead to more energy and environmental damage.

The truth is: We cannot create energy. Natural energy is the true basis of our monetary systems. When we create more money, we don’t create more resources. We simply consume resources at an ever-increasing rate. Made possible by an extraordinary, temporary energy surplus, the human economy is now over a thousand times larger than it was five centuries ago. And most of the profits now accrue to only a fraction of the population – not to the rest of humanity or future generations.

The French philosopher Paul Virilio once said: “When you invent the ship, you also invent the shipwreck; when you invent the plane, you also invent the plane crash; and when you invent electricity, you invent electrocution. Every technology brings with it its own negativity, which is invented at the same time as technological progress.”

The negative consequences of our progress are becoming ever greater. Nate Hagens describes it this way: “Reaching for our phone to see if someone liked our Facebook post or to see if Bitcoin is up or down aren’t really our goals. We are in reality just seeking the same brain rewards that led to success for our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Dopamine is a molecule that, in animals and in humans, leads to motivation and action. In a materially rich, modern world, the habituation to the action of consumption leads to the wanting of things culture – wide being stronger than the reward we get from having them. This is a fundamental problem for an economic system that’s turning billions of barrels of oil into microliters of dopamine.

Our current way of life is, from an evolutionary perspective, an exception and an anomaly – but we take it for granted because, as individuals, we’ve never known anything else.

The Great Simplification

Why does Nate Hagens call his podcast “The Great Simplification”?

He believes that the future will lead us – one way or another – to a simpler life. We will have to adapt our lifestyles to lower energy consumption. Our lives will inevitably become less global, more interpersonal, and more closely tied to natural processes.

“Many paths lead through a Great Simplification. Some are wise, humane, and even preferable to what we have now. Some are so bleak as to be almost unthinkable. Yet it is precisely reflecting on these paths and actively choosing between them that offers the only realistic hope for a long and meaningful future for humanity.

Nature has gifted us with a productive and beautiful home, with the capacity to understand how we got here, and with the creativity to imagine possible paths forward. The future doesn’t have to be dystopian, but wisdom alone will no longer be sufficient for the next stage of our journey. We need imagination, foresight, empathy, and above all, wisdom to navigate the path to the future to come.”

In his conversation with Nate Hagens, Daniel Schmachtenberger also repeatedly returns to the importance of wisdom for our future path. We recommend all of their talks, but especially this one, in which Schmachtenberger very precisely explains the differences between intelligence and wisdom (and, of course, much more).