Paul Tillich: The courage to be

Love and courage belong together. Courage is a quality of the open heart: it is its strength. Love is not weak. The word “courage” comes from the Old French word “coeur” for “heart.” Courage is an expression of our sincere, heartfelt participation in the world. Human beings constantly take courageous paths in their lives: in their relationships, in their work, in their decisions, and with themselves.

David Whyte, a contemporary poet and philosopher, writes: “There is no marriage, no matter how happy, that won’t at times find you wanting and break your heart. In raising a family, there is no way to be a good mother or father without a child breaking that parental heart. (…) So it can be a lovely, merciful thing to think: Actually, there is no path I can take without having my heart broken, so why not get on with it and stop wanting these extra-special circumstances which stop me from doing something courageous?”

And Joanna Macy:

“… love is not only about merging. It’s a noble calling for the individual to ripen, to differentiate, to become a world in oneself in response to one another…”

This “noble calling” points to an aspect of love that we sometimes forget or underestimate – it has to do witha capacity to courageously respond to the world and to another, as Joanna Macy has often put it.

What kind of life makes sense and fulfills us? If love is one of the qualities that makes our limited life here on earth worth living, why shouldn’t we prioritize it over all the things we normally pursue? To live a life in harmony with our deep values – but in a world where these values are threatened – we need courage again and again. We must stand up for them and also have the courage to say no to what threatens them.

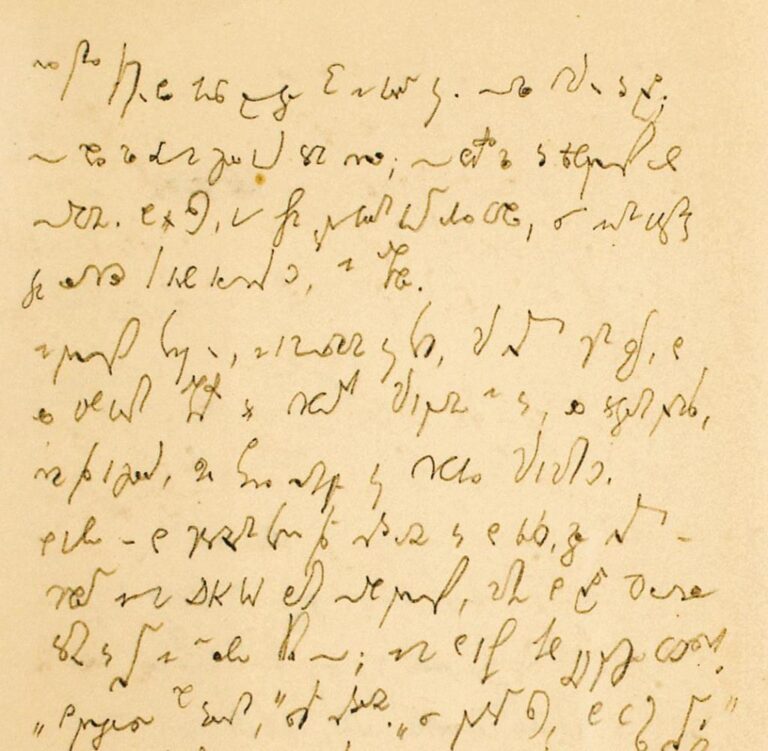

Paul Tillich: “The Courage to Be”

Paul Tillich was one of the most important Protestant theologians and religious philosophers of the 20th century. His passionate commitment to freedom made him an early critic of Adolf Hitler and National Socialism.

Paul Tillich was the first non-Jewish university professor to be banned from practicing his profession by the Nazis in 1933. As a result, he was forced to leave the University of Frankfurt – “I was the first non-Jewish academic to receive this honor,” he later expressed ironically.

Since the 1920s, he belonged to the circle of “Religious Socialists”, who demanded social justice instead of church-institutionalized welfare. Tillich wrote: “It is a higher goal to abolish the preconditions for giving alms than to alleviate poverty through alms.”

In 1929, Tillich joined the SPD. In his essay “The Socialist Decision,” he also attacked the National Socialists, so that the book was included in the list of book burnings in 1933. His support for Jewish fellow human beings, his religious socialism, and his commitment as dean of the University of Frankfurt to expel violent National Socialist students led to Tillich’s dismissal. He narrowly escaped prosecution and, with an invitation from Columbia University, was able to emigrate to the United States. From this safe haven in New York, he organized and directed aid programs for emigrants from Central Europe who fled the Nazis and emigrated to the United States in the 1930s.

As a political theologian at Yale University, he recorded 112 radio programs in German, which were broadcast in occupied Europe from March 1942 to May 1944. Even his closest friends in the United States knew nothing of this secret work for the Allies.

In 1952, he wrote his most widely read book to date The Courage to Be. In it, he speaks of an existential courage that ultimately allows us to confront and overcome meaninglessness.

“There is wisdom in courage,” he writes, and: “The courageous person sees through the illusion and distortion of fear or distress to what is truly good and acts accordingly.”

Tillich writes about the “Age of Anxiety” that we are still experiencing today. One of the most important approaches in this book is the analysis of our human anxiety, which he describes in three facets:

– ontological anxiety, the fear of death (non-being) and our ultimate fate

– spiritual anxiety due to despair and the loss of meaning

– and moral anxiety, the fear of guilt and condemnation due to our inevitable implicatedness in human moral misconduct

Courage, in his view, is the honest and conscious confrontation with these fears and the decision to assert one’s own being in the face of the loss of values – values such as security and trust in authority, democratic values, and the meaningfulness of life’s circumstances.

The courage to persist despite and in the face of fear

This certainly applies to his time as much as it does to us today. We often don’t want to feel feelings like fear and threat – and close our hearts to them. That’s human, but it also means that we are trapped by defense mechanisms and reactivity. We are not fully here, not fully with ourselves, and in a certain sense, that´s exactly what it is about: we don’t want to be fully here either, not with all these difficult feelings.

However, Tillich encourages us to take on fear, despair, and meaninglessness in order to live more fully. He described this as “to take it upon oneself.” The dictionary offers more than 20 synonyms in German for this term – a summary of which could be: It is a call for each individual to face the challenge and the fears, to dedicate themselves to a cause, to commit and to deeply engage with the situation, the questions, the feelings, to explore them, and to mature from it.

This engagement, according to Tillich, is the courage to persist despite and in the face of fear.

Courage is our committed participation in life, in others, in a community, in our work, in our future; it enables us to meet the needs of our relationships and to engage in things that are dear to us: in the needs of a person, in society. Courage is not blind: It requires the wisdom to find a balance between boldness and cowardice, as Aristotle already put it.

We would like to mention an example of this quality of courage: Dr. John Gartner and Dr. Harry Segal’s podcast “Shrinking Trump” (both are psychiatrists, “shrinks”). They wholeheartedly confront all these destructive attacks on basic human values in the United States, and openly show their feelings, the fear and anger, and how they deal with them.

All of our courage lies in being authentic, staying present, and finding our personal response to the challenges and the crisis, even when difficult feelings like helplessness or fear arise: then we may want to defend ourselves through avoidance and isolation. We believe this protects us from danger, but in reality it only protects us from the perceived threat of emotional pain.

But with a closed heart, we also lose – without realizing it – access to the qualities of an open heart: the courage and strength to stand up for ourselves in a sociable way; we also lose loving kindness for ourselves and appreciation for others. Paul Tillich remained open until old age, including to other perspectives and religions.

He wrote: “I was in Japan, where I debated with Buddhists for ten weeks. You have to understand that every contemporary religion contains elements of what is also present in every other contemporary religion. Therefore, when you speak with a Buddhist, you are always speaking to yourself at the same time.”

He also formulated this openness as fundamentally belonging to himself:

“I feel between the worlds. And I affirm this position because it bears a great deal of resemblance to the fundamental Christian idea that we are pilgrims on earth. (…) Existence on the border, the border situation, is full of tension and movement. It is not, in reality, a standing still, but a crossing, a returning, a returning again, a crossing again, a back and forth, whose goal is to create a third, beyond the limited territories.”